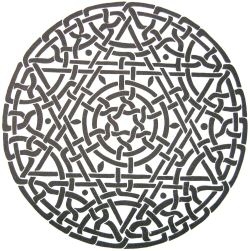

Ornamental detail from a Koran produced in Valencia, Spain 1182-3.

*

* *

Roses

in late 16th – early

17th century vihuelas: some thoughts and ideas.

One

of the most fascinating of 28 historical documents recently

published, “Inventory and valuation of the workshop

contents of the violero Mateo de Arratia of Toledo”, dated 30 June 1575

[1], contains the following entry: two new vihuelas in

Portuguese ebony, one with a sunken rose (lazo hondo) and

the other with a rose

in the soundboard (lazo en la tapa). Reference to the

type of roses used in instruments is not just restricted

to this particular account

and seems to have served as one of the main defining characteristics

(together with the instrument’s body type) in descriptions

of the vihuela and the guitar. In certain cases, as we will see further,

apart from being a purely constructional reference, it also tells

us how the makers’ skills and abilities were judged and differentiated.

The main purpose of the present study, however, is to try to establish

what could have been meant by these two definitions: ‘lazo

hondo’ and ‘lazo en la tapa’.

Firstly ‘lazo

hondo’; the most obvious analogy that

comes to mind is a type of multi leveled rose with progressively

descending patterns into the inside of the instrument’s

body. Roses of this type can be found on a relatively large number

of surviving

instruments, not only guitars but also citterns, harpsichords

and even viols from the late 16th - early 18th century. Most

often these “three-dimensional” roses

are made entirely of parchment although occasionally upper

layers of their ornamental patterns could have been made

of wood as well.

The other type of the rose, which is equally well represented

on the instruments of the above-mentioned period, consists,

as a rule,

of several very thin layers of wood and parchment arranged

in a sandwich-like way. It does not sink so deeply into the

inside of the instrument

(the overall thickness of the rose of this type can be as

little as c 1.0 mm) but is set just below the beveled edge

of the sound

hole [see images 1, 2 & 3]. Therefore,

to a certain degree, it can also be classified as ‘lazo hondo’ but

whether this is really so will remain to be determined. The

rose on the vihuela E. 0748 from the collection of the Cite

de la Musique

belongs to this latter type [2]. Only small fractions of

the rose on the Quito vihuela are preserved, so one can not

be exactly sure

of its original method of construction, although from what

looks like fragments of parchment around the perimeter of

the sound hole,

it could have been of a sunken, ‘lazo hondo’ type

[3].

The

presence of these two types of roses on the earliest surviving

guitars is particularly important for us because their constructional

features (and, as a result, their acoustical properties too)

may well be in many ways very close, if not identical to those

of the

late 16th – early 17th century vihuelas [4]. This idea

of similarity of approach to the construction of the vihuela

and the guitar is

evidenced, for example, in the “Certificate of

examination of Juan Rodriguez” of 27 December 1578 which states that: “… examiners

of the craft of violeros … have examined the journeyman Juan

Rodriguez in the making of a vihuela with a sunken rose and a guitar

in the same manner…(una bihuela con lazo hondo y en

una guirarra de la misma manera)” [5]. Although, apart from the type of

the rose, no other distinct characteristics of the instruments

are given, they were most probably of a plain (llana) type, in

other

words, with flat backs. This point becomes more evident from the

account that follows below and can be further exemplified by the

fact that this examination was carried out on a journeyman, who

was only about to embark on his new career as an independent violero.

The “Certificate of examination for the violero Pedro Tofiño” of

1588 presents us with a more differentiated approach when it comes

to the matter of roses and may bring us a bit closer to understanding

why the choice of rose type was such an important issue: “The

said overseers and examiners … have examined the said Pedro

Tofiño on a plain vihuela and on a cittern with a sunken rose

(una vihuela llana y una citara con lazos hondos), which the said

Pedro Tofiño made in their presence, … and … agreed

and gave him a licence and faculty, as an accepted and examined master

craftsman in the making of a plain vihuela and a cittern with only

sunken roses, so he can, from this date onwards, freely make and

repair only that type of instrument … without hindrance or

penalty, as long as he does not make viols, harps or vaulted vihuelas,

or decorate the table with inlays, or with carved roses (no pueda

haver biguela de arco ni arpa ni biguela aconvada ni echar ataracea

ni lazo en la tapa) until he is examined again …” [6].

What

we may learn from this account first of all, is that

the level of a maker’s skill was measured by his ability

to execute certain carving procedures (as such instruments from

the ‘prohibited’ list,

as viols and harps would certainly require a higher

level of competence not only in carving but equally more complicated

assembling techniques).

As for the inlays (ataracea in this particular context

can also be interpreted as intarsia or mosaics),

they clearly denote (see also

Toledo 1617 account below) more elaborately made instruments,

for which this particular maker would still need to gain the

necessary

skills. In a way, the wording of the account seems

to echo the rather austere external features of the surviving

E.0748 vihuela (albeit

with a vaulted and fluted body) – plain, undecorated

soundboard with a “sunken” (?) rose and

with no ornamental inlays. Even more so, the very fact

that the sunken rose (lazo hondo) is

mentioned on both the vihuela and the cittern, with

no indications of the violeros’ own involvement

in its making, may simply mean that those roses were

already supplied pre-fabricated by craftsmen

of a dedicated trade [7]. Although no deep sunken rose

is present on the surviving vihuelas (except, perhaps,

on the Quito vihuela?),

they are well represented on both the early 17th – mid

18th century guitars as well as late 17th – early

18th century citterns.

As

for the “lazo en la tapa”, the apparently logical

interpretation that first comes to mind is for a “rose cut

in the soundboard wood”, in a similar way to roses in soundboards

of lutes. But can we really apply this seemingly obvious analogy

to the case of vihuelas? Neither iconographical nor written sources

are sufficiently detailed to provide any clearer idea for this important

but rather subtle organological feature of historical vihuela construction.

A fair degree of confusion, however, would inevitably arise if we

tried to imagine the lute-type of the rose in the soundboard of the

late 16th – early 17th century vihuela as well as its closest

historical companion - the guitar. No “lazo a la tapa”,

which is cut directly into the soundboard wood, is present on any

surviving guitars from the early 17th century onwards (please correct

me if I am not right!). It doesn’t even seem reasonable, taking

into account a fairly large number of surviving early – mid

17th century guitars, to admit the presence of a

rose of this type on the soundboard; the construction

of which is so fundamentally

different from that of the lute.

The

barring arrangement of the vihuela and guitar soundboard

as well as its thickness differ quite dramatically from a typical

lute

soundboard. The E.0748

vihuela has just two bars with “wedge” shaped bar end supports on the

sides of the instrument and a soundboard thickness ranging from 3.5

mm in the central area to 2.0 mm on the edges. Two soundboard bars

in combination with “tuning-fork” shaped bar end supports

are found on the Quito vihuela [8] and on one of the earliest surviving

late 16th – early 17th century Spanish guitar in the Convento

de la Encarnatión, Ávila [9]. Although

the original soundboard on the Belchior Dias instrument

did not survive, the

remains from the four bar end supports on its sides

suggest an identical

barring arrangement, with a possible proportional

reduction of the soundboard thickness (as compared

to the E.0748 vihuela) in

accordance

with the smaller size of the instrument.

The

two bars with accompanying bar end supports on

the sides remained, as the surviving instruments demonstrate, one

of the most characteristic

features of Spanish guitar construction up to the

mid 18th century when it gradually started to be replaced with

a fan-system of struts.

This, in turn, resulted in the use of thinner soundboards

(but still no roses cut ‘in a lute way’!) The very

idea of the two-bar arrangement would seem to preclude the use

of the lute-type of rose

altogether, both on the guitar and the vihuela.

For a rose to be cut in the soundboard of a lute, it has to be

thinned down in that

area to c. 1.0 mm, supported with a paper backing

and small bars underneath and from one to three cross bars for

its entire width.

This way of construction on the late 16th century

vihuela / guitar soundboard would look rather odd, hardly consistent

with its structural

and acoustical nature. Even if the rose is cut

in, say, a 2.5 – 3.0

mm thick spruce (!) soundboard, it would still

need to be supported from underneath with an additional barring

structure, which is again

contradictory to the idea of the two-bar arrangement.

Neither of these ways nor any traces of such have survived, at

least to my knowledge,

on the early 17th – mid 18th century guitars

of Iberian, Italian or French origin. It simply

lies beyond the logic of those two rather

differently structured instruments - the lute and

the vihuela. Interestingly enough, on some surviving

examples of late 16th – early 17th

century viols we seem to find examples

of both ‘lazo en la tapa’ and ‘lazo

hondo’ types

of roses. The first is represented with a two-layer

(wood and parchment) rose which is set flush with

the soundboard surface, while the second,

is with a sunken rose of a three-dimensional design [

see images 4, 5 & 6].

Some insights as to what might be hidden behind the definition

of ‘lazo

en la tapa’ emerge from the “Proposal

of Ordinances for the craft of violeros of

Toledo” of 1617. The section of this

document which deals with the examination procedure in the making

of “a plain six-course vihuela (una

biguela llana de seis ordehes) “ also

defines that “this instrument has

to have inlaid rings, an ebony fingerboard

and a boxwood rose with thirty-six points (este

ynstrumento a de llevar veril y plantilla de

hevano con un lazo de

box de treinta y seis)” [10]. A further reference towards the

end of the document, which aims to provide a sort of guidance for

vihuela repair, only re-confirms the earlier statement: “… if

anyone were to bring an ebony vihuela to have

a soundboard fitted, this [soundboard] must

be of spruce *pinewood* with

a rose of boxwood and not of parchment (que

si alguno ttrujere biguela de hebano para

que le hechen tapa que se le heche de pinay

bete *pino* y con lazo de boj y no de pergamino)”.

This description may well indeed represent

the ‘lazo en la tapa’ type of the

rose with inlayed rings surrounding it for

the purpose of disguising the border

of the inserted rose made of different material

than that of the spruce *pinewood*.

In addition, a carved boxwood rose would almost

certainly be of comparable thickness and of

a similar shade of colour as the soundboard,

which would make this ‘lazo en la tapa’ way

of construction even more logical.

This account is also, in a way, consistent with the above-mentioned

description of the examination of Pedro

Tofiño on a plain

vihuela and the use of ‘lazo hondo’,

which would most probably be made of parchment.

The only difference here lies clearly

in the matter of aesthetics, which seems

to have been ruled by the choice of corresponding

materials: an ebony vihuela – a

carved boxwood rose, a simpler, more modest

instrument by the beginning violero – a

parchment ‘lazo hondo’. At

least one of the surviving sources, however,

proves that it was not always

the case. An inventory dated 1580 lists: “… an

ebony guitar with a sunken rose, together

with its case, and an inscription

on the head that reads Juan Rodriguez (una

guitarra de ebano con el lazo hondo con

un letrero en la cabeza que dice Juan Rodreguez

con su caja)” [11]. Note that neither

of the documents mentions the procedures

of making roses as such, either of parchment

or

carved in boxwood. Equally so, neither

admits an alternative

construction of the rose, one which could

be cut directly into the soundboard

wood!

Boxwood

roses are also repeatedly mentioned between

1632 – 1636

on the instruments made by Pablo de Herrera

and Manuel de Vega, apparently on a cocobolo tiplecito (small

tiple) and guitars (some of them made

of Portuguese ebony) [12]. Additional evidence

that the carved vihuela roses might have been made of boxwood

later in the 17th century is

contained in the “Inventory of

the workshop contents of Antonio de Medina

at the time of his marriage to Catalina

Rodriguez” of

1674, which lists: Ebony, box and walnut

wood to make biguelas … (Ma

en Madera de hevano box y nogal para fabrica de biguelas…) [13]. This is the only instance related

to the vihuela in this rather extensive

listing of tools, equipment, materials

and instruments

(thirty-one guitars but also two harps and two archlutes) [14].

The

mentioning of a spruce *pinewood* soundboard

in the Toledo ordinances of 1617 together with the boxwood and

parchment roses

has some additional

significance for, as we can see in some

surviving late 16th – early

17th century citterns and even harpsichords

with the soundboards made of different materials than spruce

(notably cypress and cedar

of Lebanon), their roses can be cut directly

into the soundboard [see images 7, 8 & 9].

The manner of their execution, however, is somewhat different

and is more related to the actions of

carving and sawing than cutting. Differences in the ornamental

design, as compared with a typical

lute-type of the rose are also apparent.

In addition, there is also no noticeable thinning of

soundboard in the rose area. The

choice of a different soundboard material

here fulfils the purpose: carving in

harder, rather slab-cut

wood certainly proves ‘technologically’ more

consistent than in quarter-cut spruce

or pine and this is all too clearly

demonstrated by these examples.

On

the other hand, some surviving citterns

and viols with pine or spruce soundboards display a certain degree

of consistency with

the

above mentioned accounts related to

vihuelas and are fitted with either sunken (parchment) or flat

(sandwich layers of wood and

parchment)

roses. One of the examples of the latter

type of rose which is found on the late 16th century Italian

cittern made by Giovanni

Salvatori

[15], (and is of similar construction

to the rose on the E.0748 vihuela) in this case appears to be

inserted flush with the soundboard

surface

[see image 10].

This also gives us another possible

idea of how the multi layered wood

and parchment

type of roses could

have

been used in a “lazo en la tapa” sort

of way, in addition to the above mentioned

boxwood roses of the Toledo ordinances of

1617.

Let

us now turn again to the inventory

of the workshop contents of the violero Mateo de Arratia of Toledo

of 1575. This is one of

the most comprehensive of existing

listings of what might have been found in a workshop environment

of the 16th century Spanish

violero and it clearly shows

that this maker was almost certainly

of a higher degree of qualification

than,

for example, Pedro Tofiño of

Madrid. As for the subject of roses,

there is the following entry: Fourteen gouges thirteen with

boxwood handles to make roses and

one for general work (Qatorze guvias

las treze de hazer lazos con sus

qavos de boz y una del oficio).

Just to complement this, A

round piece of boxwood a yard long

with two other pieces half-sawn (Un

pedazo de box rredondo de una vara

de largo con otros dos pedaços

empeçados aserrar) is

also listed in this account. The

shear amount of these tools seems

hardly necessary for carving the

lute-type

of the rose, in particular in such

material as spruce. However, they

would certainly prove useful either

for cutting (some of these ‘gouges’ might

also be used as ‘punches’)

multi layered wood and parchment

or boxwood roses. The signs of usage

of these kinds of tools can

be seen on some original roses [see image 11].

A

similar set of tools for carving

roses is also mentioned almost one hundred years later in the “Inventory

of the workshop contents and belongings of Joseph Gonzalez made

after the death of his wife

Isabel de Ortega” of 1670 that lists “Nine gouges to

carve roses, one large and a broken burin” (Nueve

gubias de hacer lazos y otra gubie

grande y un zincel quebrado)” [16].

The

other entry from the account of

Mateo de Arratia of Toledo which, in a way, brings a totally different

dimension to our understanding

of how Spanish violeros approached

their business, by integrating trades from their recent imperial territories

- in this case from

none other than Venice! It reads

as follows: “Eighty-eight

tops from Venice with roses, at

three and a half reales (Ochenta y ocho tapas de las de venicia

con sus lazos a tres reales)”,

apparently the most expensively

valued entry of the account, at the equivalent of 10472 Maravedis.

Stocks

of soundboards are also mentioned in a number of other historical

accounts published in [1] but only that of Mateo

de Arratia informs us where they may

have originated from. There is no direct

reference in the surviving Ordinances that the

violeros were allowed to use ready-made parts, but it may be

that it was possible after they had

reached a certain degree of status in their career [17].

From

the names of the instruments

as well as the other items of equipment listed in the inventory,

it appears that at least the following

instruments were being made

in the workshop of Mateo de Arratia: vihuelas, guitars, citoles

(citolas), citterns (citara) and small

gitarrones (gitarrones

peqeños). At

the time being, it is only

possible to guess whether

such a massive stock of soundboards

had been prepared for vihuelas,

citterns or for the growing

demand

in guitars. One fact in relation

to roses, however, deserves

mentioning. The basic pattern

of the ornament of the rose

on the soundboard of

the E.0748 vihuela [18] is

identical, at least to my

knowledge, to roses in several

other surviving instruments:

two guitars, an Italian

harpsichord and a mandolino [see

image 12].

Therefore the possibility

is not excluded

that the

parchment roses mentioned

in the above quoted accounts

(or at least some of them)

were made

outside Spain, while those

carved of boxwood were supposed

to be made by the violeros

themselves and represented

the uniquely Spanish

trend in the historic vihuela (and, possibly, guitar) making

traditions.

At

least three varieties

of roses seem to have been used in the vihuelas and the guitars

made by the Spanish violeros in the late

16th – early 17 century:

1)

multi leveled“three dimensional” roses

made entirely of parchment,

2) multi layered“sandwich” roses

consisting of thin

layers of wood and

parchment,

3) roses carved of a solid piece of boxwood.

The

first and third types

are more likely to be associated with what the original sources

name as ‘lazo hondo’ and ‘lazo

a la tapa’ accordingly. The second type can possibly be classified

either as ‘lazo hondo’ if the rose is attached to the

inside of the sound hole, or ‘lazo a la tapa’ if it is

set flush with the soundboard surface. The third type is the most

likely candidate for the ‘lazo a la tapa’ type

of rose. The first

two types could have

been made either

by the violeros themselves

or, more likely, by craftsmen of the dedicated trades, while the

boxwood roses seem to have been made exclusively by the violeros. References

to boxwood roses

in Spanish documents

throughout the 17th

century and their

apparent absence

on the surviving

early – late

17th century Italian and French guitars may indicate that this type

of rose was uniquely reserved for the late 16th – early

18th century Spanish

vihuela and guitar

making tradition.

As

the use of harder

varieties of wood other than quarter-cut spruce or fir (such as

cypress) on gut-strung plucked instruments

of the

late 16th – early 17th centuries (namely guitars and vihuelas)

does not seem to coincide with their constructional and acoustical

principles - as is overwhelmingly manifested in the surviving vihuelas

and early 17th century guitars; the use of roses cut directly into

the soundboard wood equally seems as an unlikely idea. Therefore

the association of what historical sources describe as ‘lazo

a la tapa’ with

roses cut directly

into the soundboard

wood should most

probably be ruled

out.

[1]

José L.

Romanillos

Vega & Marian

Harris Winspear:

The Vihuela

de Mano and

the Spanish

Guitar (VMSG),

The Sanguino

Press, Guifosa 2002, pp. 479 - 482

[2]

Illustrated

in Aux origines de la guitare: la vihuela de mano, Cité de

la Musique, Paris 2004, p. 67

[3]

Illustrated

in The Spanish Guitar, New York – Madrid,

1991 – 1992

[4]

The idea

that the vihuelas could also have been re-used as guitars, on

the wave of the growing popularity of the latter towards

the

end of the 16th – early 17th century, is vividly expressed

in the following document, Declaration by the examiners

of the Guild of violeros about the examination of Francisco de

Lipuste: “The

said

examiners exhibited and demonstrated in my presence as notary,

one instrument

which at the moment is strung as a guitar but was constructed

by Francisco de Lipuste as a vihuela; it is, at present,

strung

as a guitar to make it easier for the said Francisco de Lipuste

to sell – he

has tried,

and is

still

trying,

to sell

it …” (see

pp. 469 – 471

of VMSG).

I will

give

more

in-depth

analysis

of the

constructional

features

and their

acoustical

implications

in relation

to late

16th – early

17th

century

vihuelas

and guitars

in a

separate

publication.

Those

who are

interested

in this

subject

can also

read

J.Romanillos’ own

reflections

on the

related matters in the prologue section of VMSG.

[5] VMSG, op.

cit., pp. 449, 450

[6]

VMSG,

op. cit., pp. 451 – 454. Note that “lazo en

la tapa” was ‘automatically’ translated here as “carved

rose” although no such precedent is given in the text.

[7]

A rather later source “Deed of capital assets that

Marcos Antonio Gonzalez took into his marriage with Doña

Phelipa Gonzalez” of

1766 lists: Roses

and glue at one hundred reales

(De lazos

y cola en cien reales). See VMSG,

op.

cit., pp. 511, 512

[8] The

Spanish Guitar, op. cit., p. 43

[9] VMSG, op.

cit., p. xxiii

[10] VMSG, op.

cit., pp. 439 - 441

[11] VMSG, op.

cit., p. 343

[12]

Cristina Bordas, La Construccion de Vihuelas y Guitarras

en Madrid en los siglos XVI y XVII, in La Guitarra en la Historia

(volumen

VI), Córdoba 1995, pp. 59 – 62

[13] VMSG, op. cit., pp. 501 - 504

[14]

The mentioning of two names biguela as opposed to guitarra in

the same account may proof that vihuelas were still being made

even in the late 17th century albeit in very small quantities

in proportion to guitars. This also seems to contradict to commonly

held belief that the names guitar and vihuela were used in the

late 17th – mid 18th centuries interchangeably. However,

we may never be able to proof the exact way of tuning of those

late vihuelas.

[15]

In the collection of Musée de la Musique, Paris.

[16]

VMSG, op. cit., pp. 497 – 500

[17]

See also: Peter Kiraly, “Did lute makers just assemble

their lutes?” Lute News, No. 53

[18]

The pattern is based on a “three-petal” flower

design which is repeated in six segments.

* * *

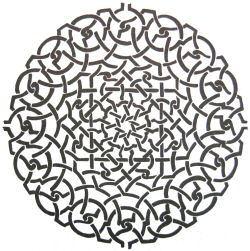

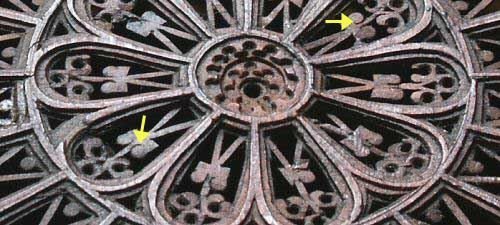

Design

on a bronze bowl, Iran, early 13th century.

* * *

© 2004

Alexander Batov

|

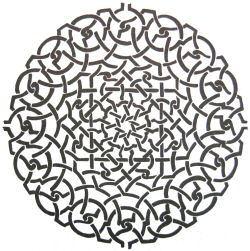

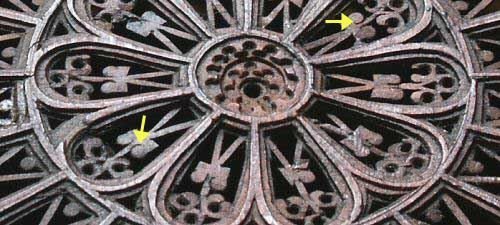

Image

1. Multi

layered wood and parchment rose on a mid 17th century Italian guitar

ascribed

to the Sellas family

of makers which were active in Venice from

the first quarter of the 17th century. It consists of five layers

(wood / parchment /wood / parchment / parchment) and is similar

in construction to

the rose on the E.0748 vihuela (Cite de la Musique,

Paris), the only

difference

being that

the

latter is made of six layers (wood / parchment /wood / parchment

/wood / parchment).

Image

2. A) Scorch

marks around the perimeter show that a pointed hot iron was used

during the rose attachment to the soundboard (causing the glue

to set more quickly). Similar technique was also used for

fixing small bars supporting the roses of lutes.

B) Parchment “re-enforcement” of

underlying cypress (middle) layer.

Image

3 The

basic division marking (of a circle in sections and concentric

rings) for the pattern of this rose was scribed by the maker directly

onto

the

upper layer

of

wood with the help of a sharp pointed tool and a pair of dividers.

The two layers of cypress (each of which is re-enforced with very

thin parchment from underneath) with the grain arranged in a crosswise

direction are clearly

visible

here.

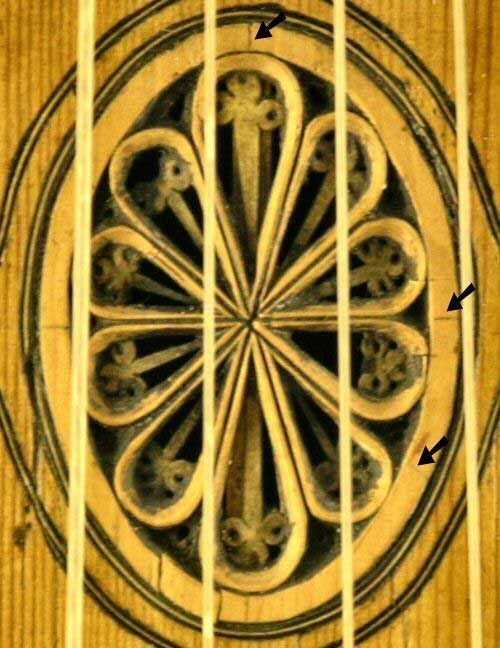

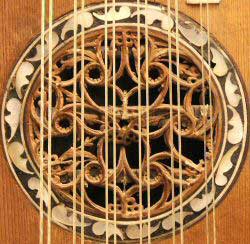

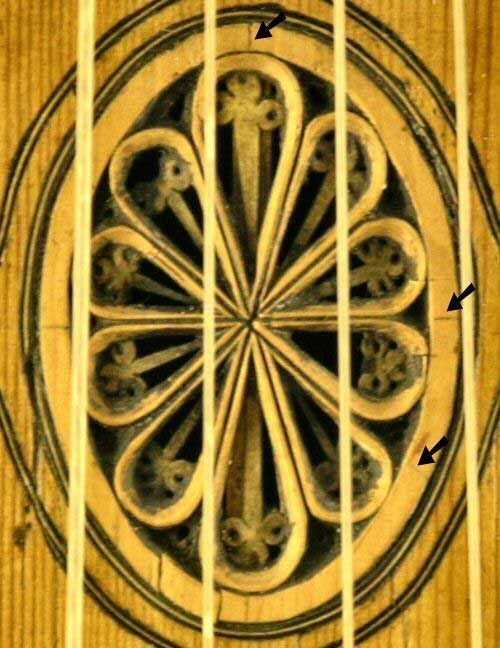

Image

4 Two-layer

wood and parchment “lazo a la tapa”rose on a tenor

viol by Henry Jaye, 1667 (V&A

museum, London). The upper layer appears to be made of boxwood,

also note tracing lines made with a sharp point, similar to those

found

on

the rose of the Sellas guitar (see image 3 above).

Image

5 Two-layer

(wood / wood or parchment?) “lazo a la tapa” rose on

the late 16th century viol attributed to Gasparo da Salò, Brescia

(Ashmolean museum, Oxford).

Image

6 Sunken “lazo

hondo” rose on a Venetian 16th century viol (Ashmolean

museum, Oxford). Also note square mosaic inlays similar to those

on the soundboard of the Jaquemart-Ándre vihuela.

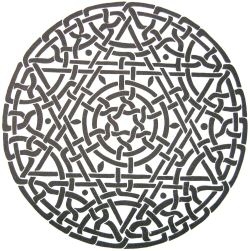

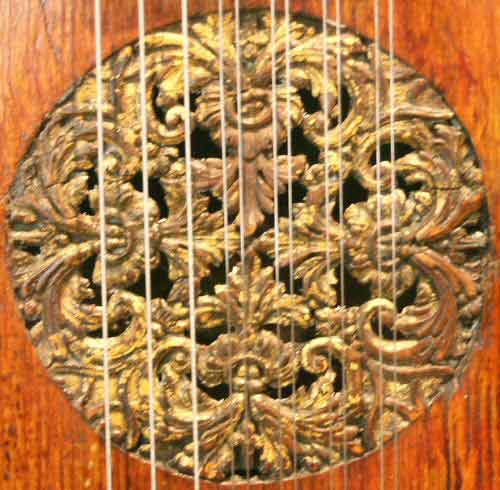

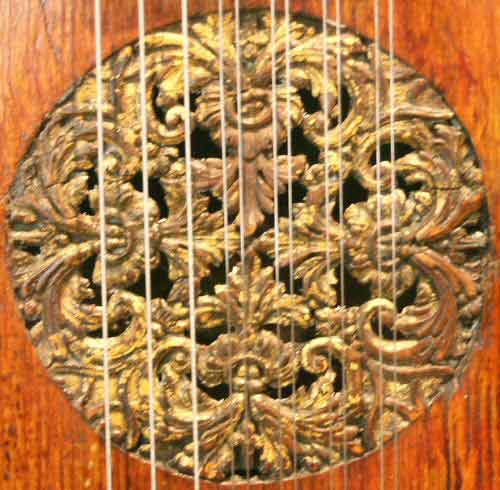

Image

7 Carved

and gilded “lazo a la tapa” rose on the late 16th

Italian cittern by Gasparo da Salò (Ashmolean museum, Oxford).

Image

8 Carved “lazo

a la tapa” rose with underlying layer of parchment

on an anonymous mid - late 17th century Italian cittern from

the V&A

Museum: note that this rose is cut through the entire thickness

of the

soundboard (i.e. no noticeable reduction of soundboard thickness

in the area of the rose). In this case the layer of parchment on

the underside seems to serve both decorative and constructive

functions.

Image

9 Carved

and / or sawn “lazo a la tapa” rose on an Italian

c.1550 spinet (V & A museum, London). As

with the rose illustrated above, this example also appears to be

cut through the entire thickness of cypress soundboard.

Image

10

Multi layered wood and parchment rose used in a “lazo

a la tapa” way, as found on the 16th century Italian cittern

made by Giovanni Salvatori (Cite de la Musique, Paris).

Image

11 Signs

of usage of gouges on the bottom parchment layer of the rose from the

mid-17th century

guitar ascribed to the Sellas family

of makers (see also images 1, 2 & 3 above).

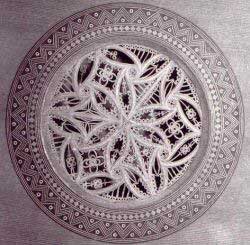

Image

12 Clockwise

from top left picture: mid 17th century Italian (or Spanish?) guitar

(Deutches

Museum, Munich), 16th

century Italian spinet (Kunsthistorishes

Museum, Nuremberg), mandolino by Francesco and Guiseppe

Presbler, Milan 1778 (RCM, London), mid - late 18th century

Spanish guitar* (private collection, Spain).

*

Many thanks to Jaume Bosser for allowing to publish this photograph.

|